Post written by Jenny Hannifin, Archive Assistant.

Creating Family Archives, Part One

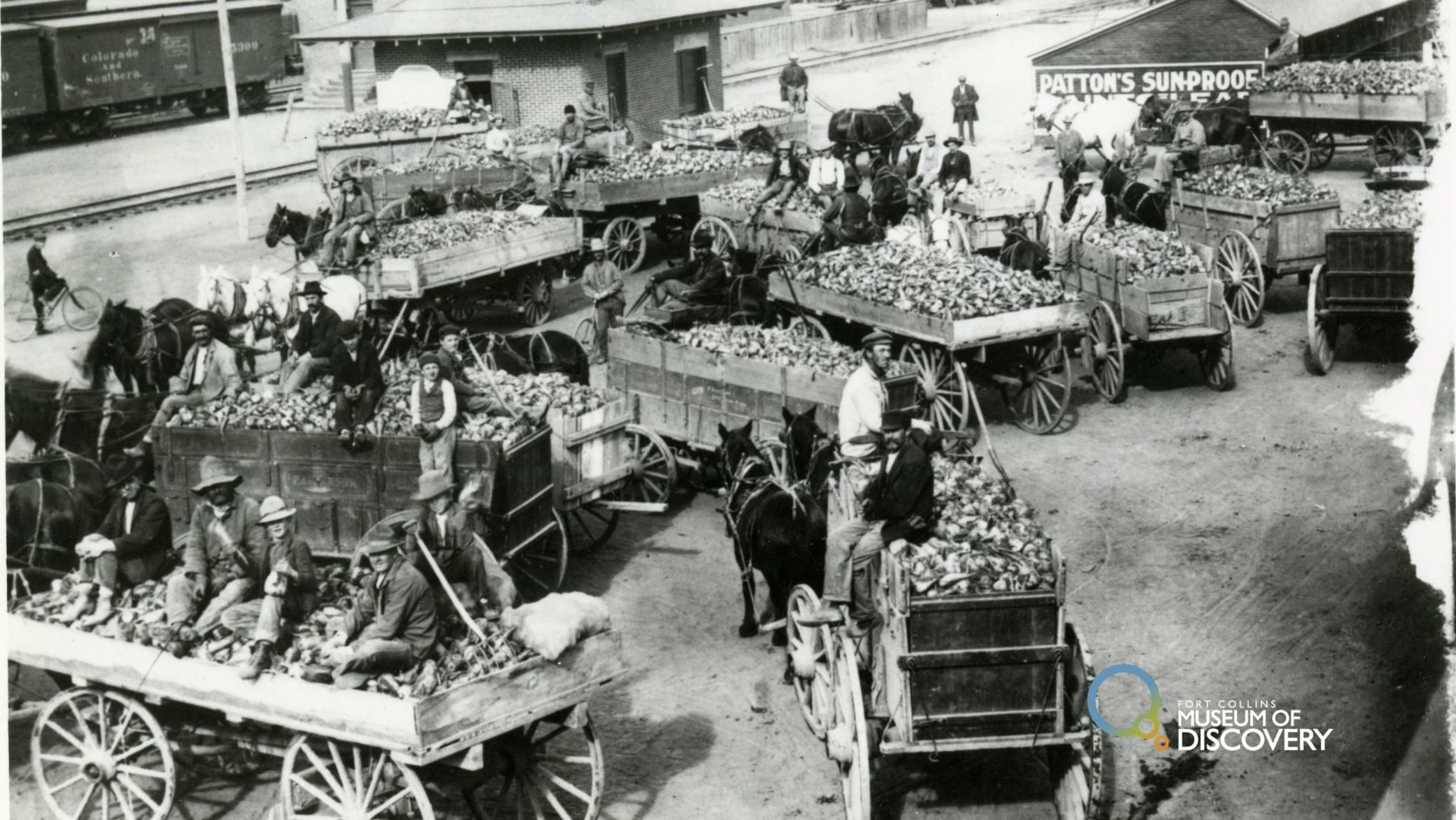

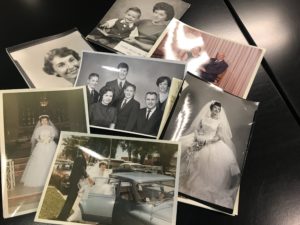

Primary sources – letters, emails, photos, scrapbooks, programs, pamphlets, dance cards, etc. – reveal wonders, and preserving and organizing them is a forever-gift. When you decide to create personal archives, you are committing to a rewarding and valuable task.

But how do you get started?

Margot Note recently published a book called Creating Family Archives: A Step‐by‐Step Guide for Saving Your Memories for Future Generations published by the Society of American Archivists. You can find details about the book here. Margot Note is an archives and records management consultant in New York, and a professor in the graduate Women’s History program at Sarah Lawrence College.

In this blog I will summarize some guiding concepts from Margot’s book to help you get you started.

What are your goals?

Personal archives can capture many things. Are you interested in storytelling and preserving memories? Are you hoping to create an instrument of legitimacy (like genealogical evidence), or to document someone’s specific legacy? Do you want to highlight the roots of your self-identification and cultural values? Is it an institution you want to document, perhaps one you were intimately involved in?

The more you conceptualize the final product, the easier it will be to devise the steps required to get there. Each of the goals listed above would have a different approach to saving, processing, and preserving materials.

What do you save?

There are three archival principles that can guide you in deciding what to save: that the item is original, reflects daily life/lives, and is of enduring value.

Original means there is just one copy of it, and it doesn’t exist anywhere else.

Reflecting daily life/lives means that it initially began life as a record of some sort and wasn’t created with the public in mind (like published materials).

Enduring value is probably the hardest to determine. In short, it means “value as evidence,” or “a source for historical research;” something that has value AFTER the creator has finished with it. Note says “For organizations, for example, only about 5 percent of records created in the course of business have enduring (archival) value. The same may be said of the records that you and your family create in the course of your lives. Among the receipts, invoices, notes, and selfies you take or receive during your lifetime, only a sliver is worth saving forever.” (Note, p37)

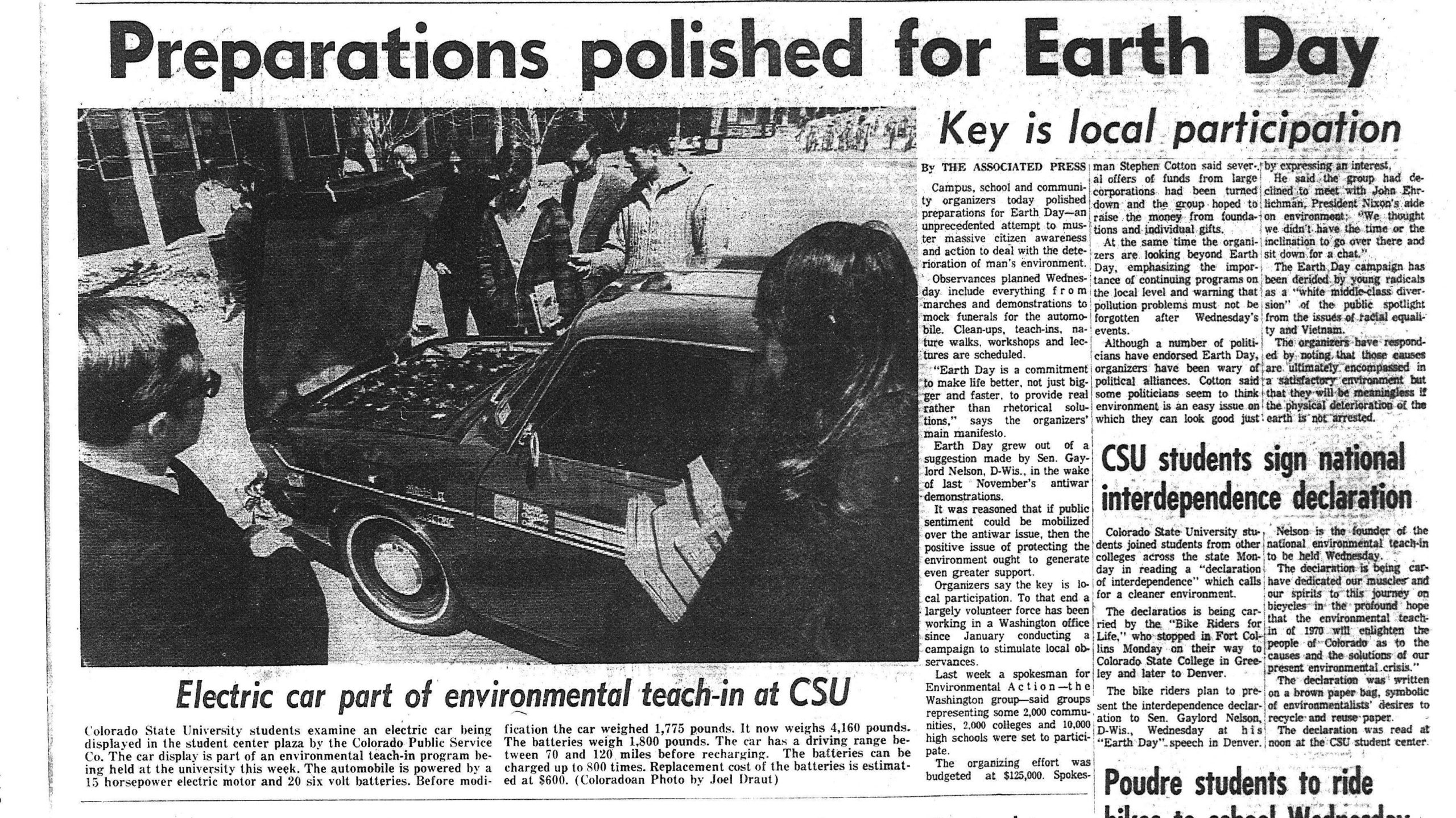

All items that you save, and that reflect these values, are format independent. In other words, a 50-year-old newspaper clipping may be less important to save than an email from last month, depending on your goals. Things don’t have to be “old” to be of enduring value – archival records can be born-digital, in the present.

Create a plan

Once you know what you want to do, and (roughly) what you want to save, you need to create a plan. Start by surveying what you have gathered. Can you divide the project up into different parts, so it is less overwhelming? How many folders or boxes do you need? Would it be easiest to create and store your project digitally?

MPLP (more product, less process) is an archival guiding principle whereby you take care of the most important things first, without feeling like you must get it all done at once. For example, start by stabilizing and re-housing fragile items, storing items by groups in separate boxes, and creating brief inventories. Later you can dive deeper with descriptions, etc. – but in the meantime, you’ve made a start.

Note suggests creating a month by month plan to stay organized. Here’s an example (Note, p6):

- August: Survey the collection; buy archival supplies

- September: Organize and process the collection; rehouse slides in archival enclosures;

create a guide - October: Select images for scanning; digitize images

- November: Interview Person A and Person B; transcribe the best selections of the interview

- December: Create memory book with photographs and interview quotes; give the books to Person A, Person B, and other relatives

Moving forward

I hope this has been useful! In a future blog we will discuss best practices in handling materials, storing materials, and related topics.

To learn more right now about materials most subject to damage, go here. To learn more about where to buy archival materials (like acid-free folders and plastic sheets), go here.

There is so much to know in this area that we will offer later this year a workshop called Caring for Your Family Treasures. So stay tuned for dates and details on our website calendar!

Continue Reading