Fort Collins and the Flu, Part III

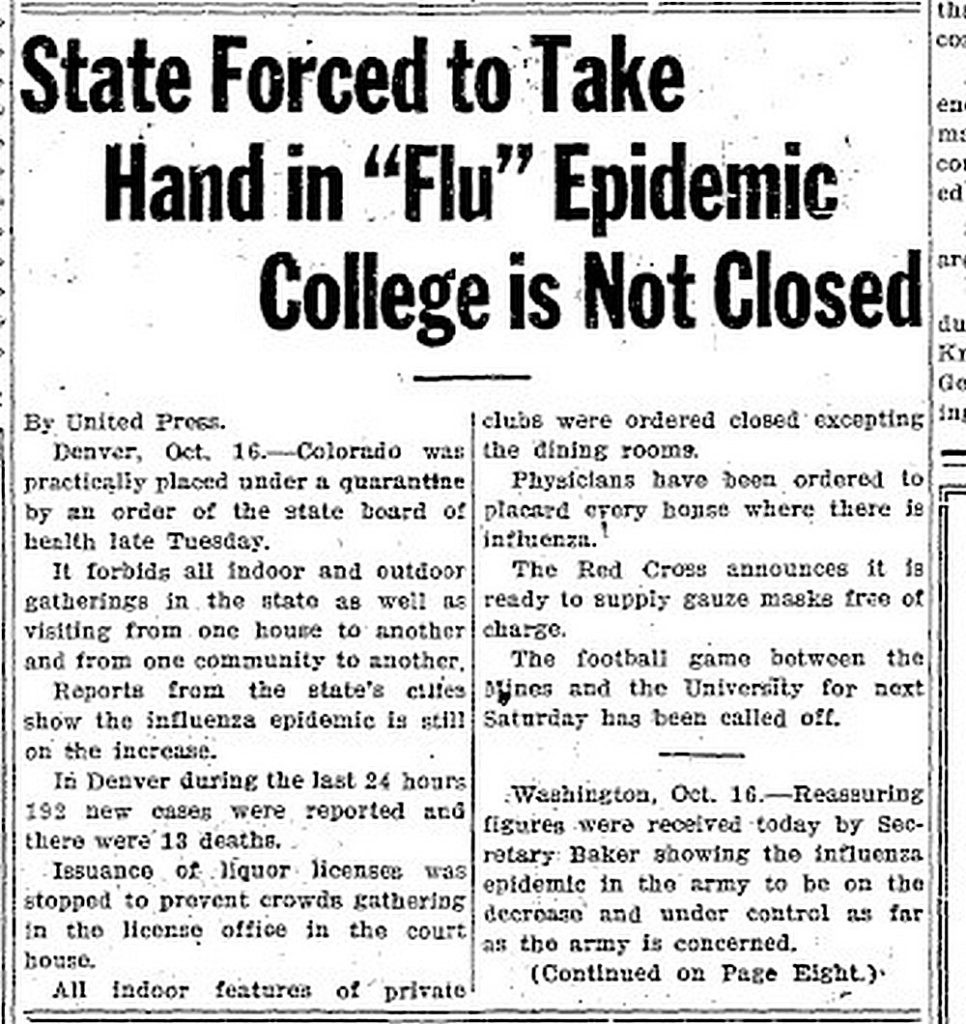

The fall of 1918 was a fearful and exhausting time for the residents of Fort Collins. Worldwide, according to Laura Spinney in Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and how it Changed the World, most of the deaths caused by the “Spanish Flu” happened in just a thirteen-week period from September through December 1918. Government authorities most everywhere were overwhelmed, uninformed and unsure, crippled by nursing shortages, lack of hospital beds and local physicians overburdened with their own patients.

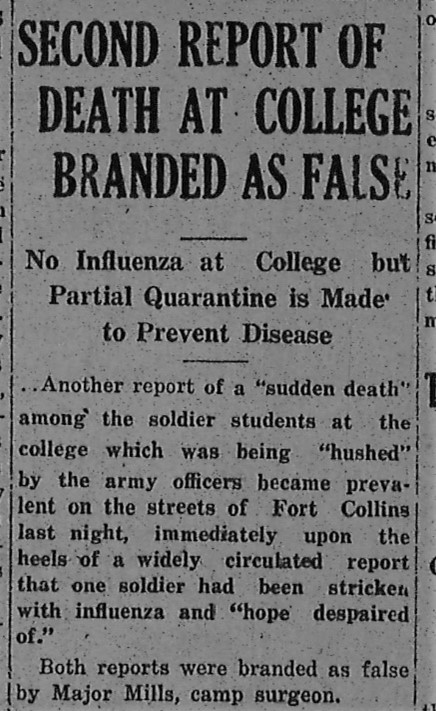

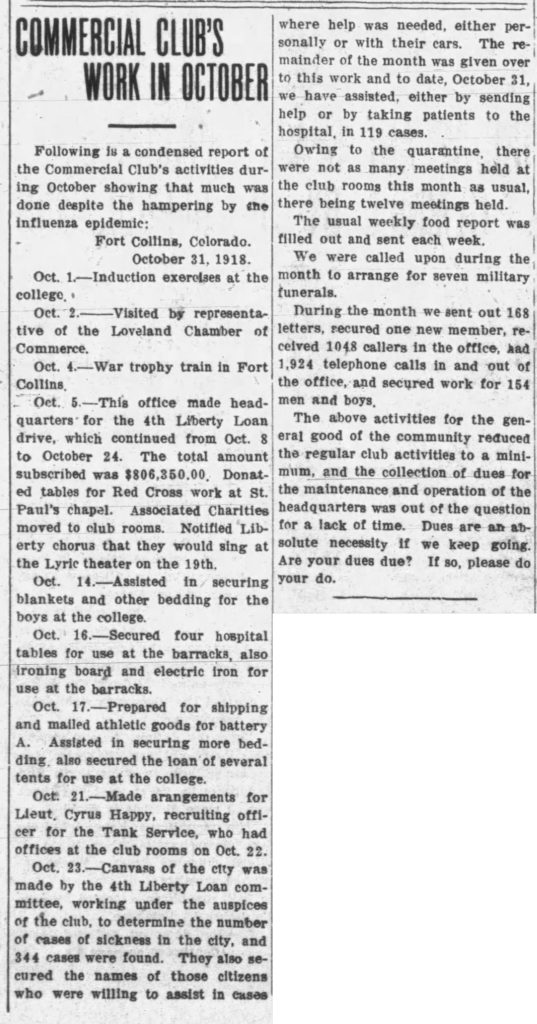

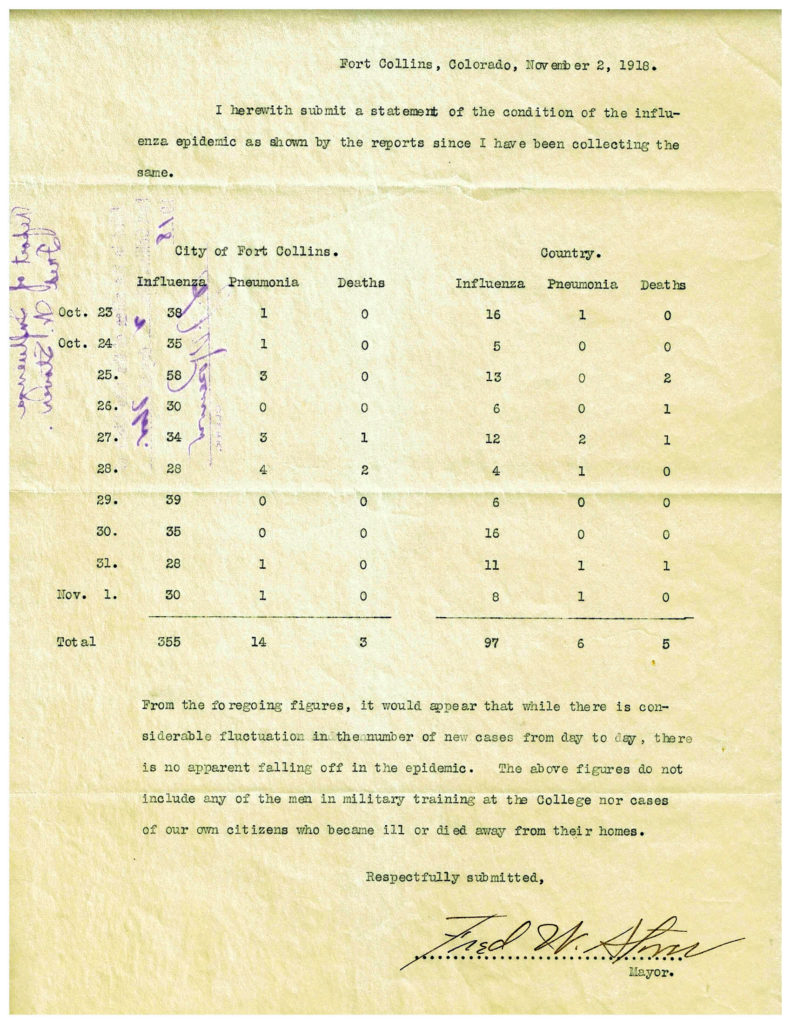

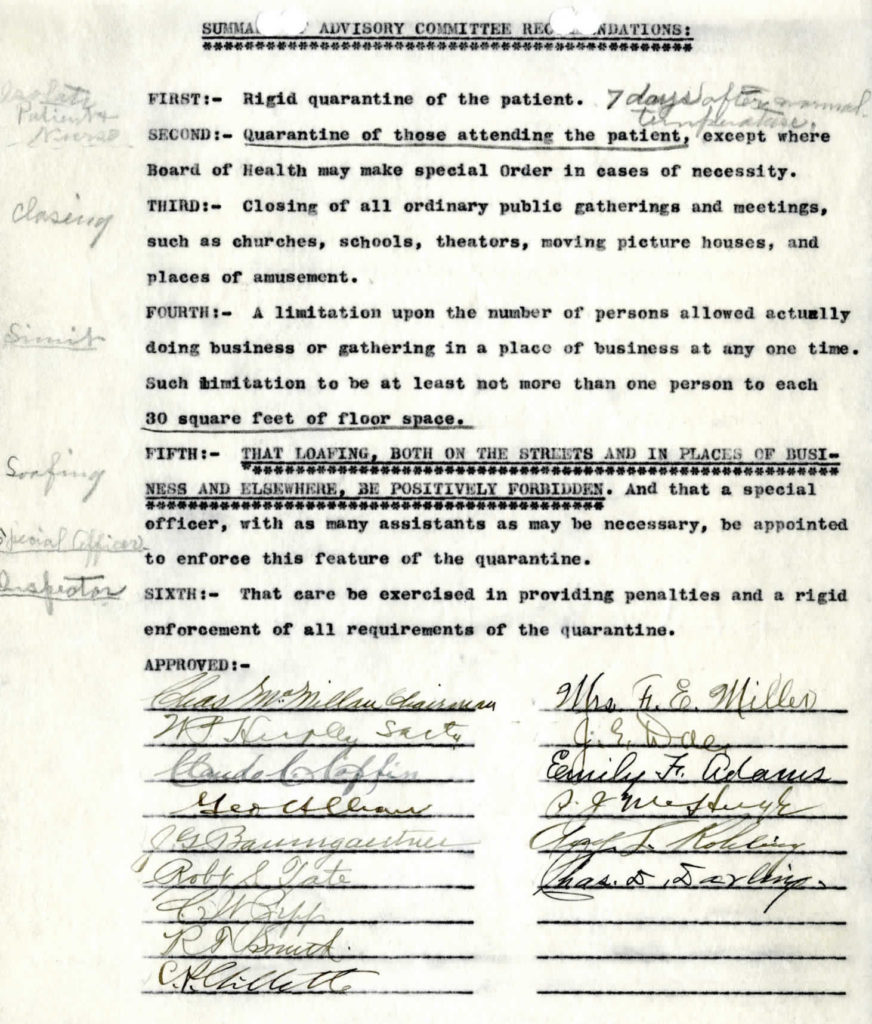

In Fort Collins, doctors were supposed to make daily reports of influenza cases and deaths to city officials so that people like the city physician, Dr. Gooding, and Mayor Fred Stover could make informed policies, but the city and county doctors were too busy tending to ill patients to make those reports (Fort Collins Express, October 23). Ruth Margrave, in an oral history recorded in 1974, recalled that her father, Dr. Wilkin, hired a driver for his car that fall as he “…didn’t drive at all during that flu epidemic. He just slept between calls, between patients.” Besides stress and exhaustion, doctors and nurses were risking exposure to the flu by caring for the sick and at least one Fort Collins doctor, Dr. D’Armond, died from contracting the flu. The Weekly Courier called Dr. D’Armond’s death a “sacrifice to the service of humanity.” (October 24).

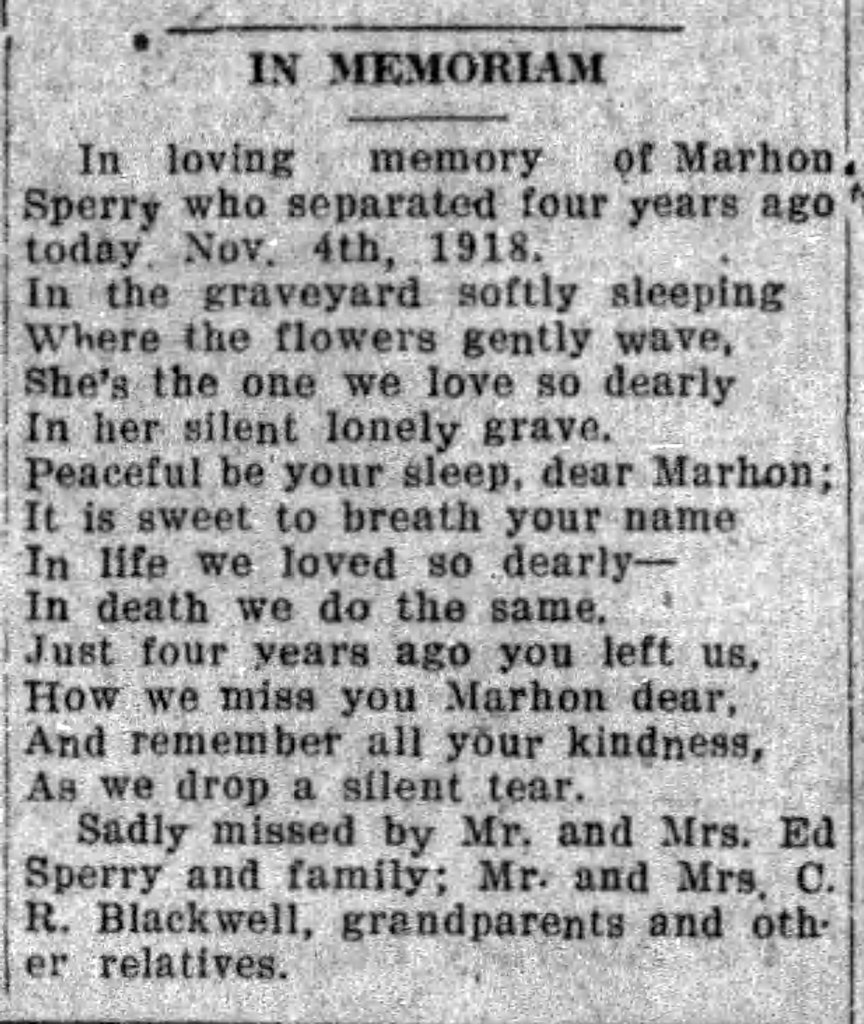

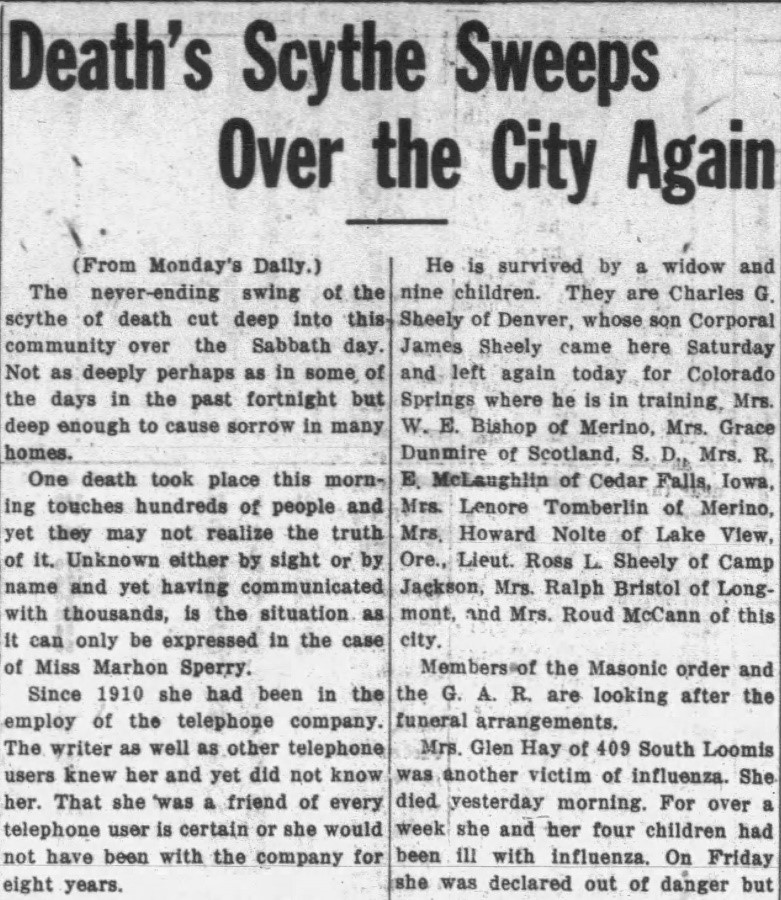

There were, of course, other flu deaths in Fort Collins during the fall of 1918. Dr. Lory of the agricultural college, lost many members of his sister’s family, including his three-year-old twin nieces (The Weekly Courier, November 29). Influenza victims often included youths, and people moved to Fort Collins to start school, or parents and professionals in their late twenties and early thirties. The writers on staff at The Weekly Courier were clearly bothered by the death of Miss Marhon Sperry, an operator for the telephone company in town, as seen in their early November column about influenza deaths.

Even with all the illness, death, pain, sorrow, and exhaustion that the people of Fort Collins dealt with through the fall and early winter of 1918, the city was relatively lucky when it came to the numbers of those sick and deaths, although perhaps not known at the time. Current twenty-first century estimates for cases during the epidemic have worldwide an average of one in three people got sick with the flu, while somewhere between “2.5 and 5 percent of the global population” died from the illness. (Laura Spinney, p. 4). The numbers in Fort Collins show a much lower death rate.

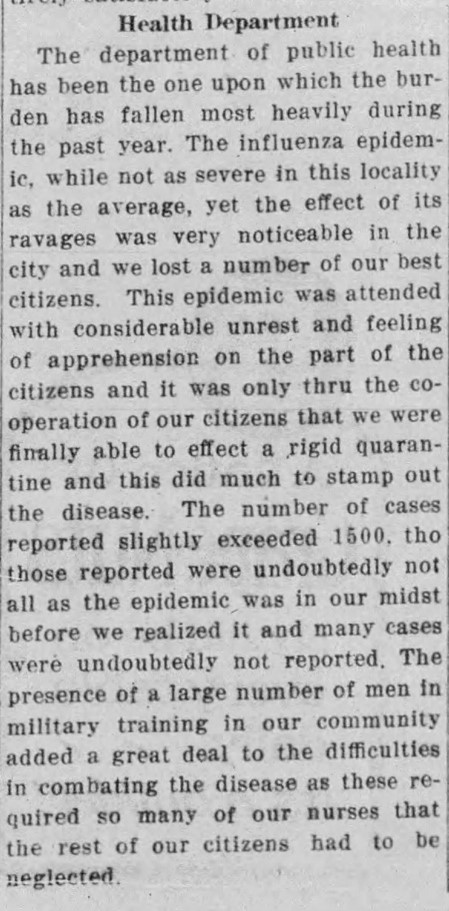

In his Annual Report at the end of July 1919, Mayor Stover gave that the total number of cases from the influenza epidemic “slightly exceeded 1,500.” (Fort Collins Courier, July 29). Some 1,100 of those cases happened in October and November of 1918. With a population hovering around 8,500, the infection rate was closer to one in five, rather than one in three. Deaths were also less likely, as Mayor Stover did not bother to provide a number for those who died in his annual report, rather just expressing sorrow at the loss of life that had happened. (A Coloradoan article from April 16, 2020 estimated 150 deaths from the fall and winter.) A caveat- the numbers given for illness and deaths throughout the epidemic in Fort Collins do not often include cases that happened at the agricultural college.

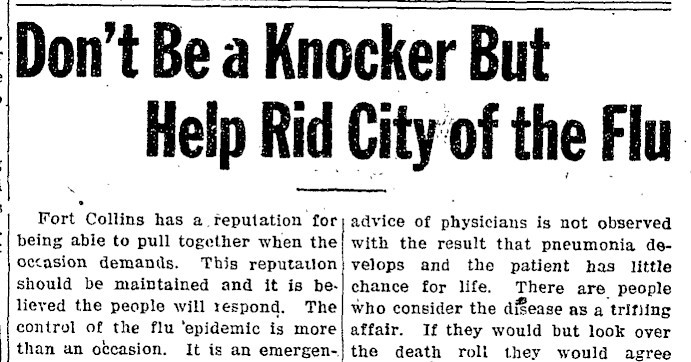

Although Fort Collins did have lower infection and death rates throughout the epidemic than other places, the comfort we can see in numbers looking back over a hundred years likely did not exist for those living through the epidemic. Even if residents of Fort Collins understood at the time that their cases numbers were relatively low, numbers, in and of themselves, can do little to override personal experience. Of the oral histories we have in the Archives that mention the 1918 flu, one stands out especially. Interviewed in 1981, Grace Davis recalled that her mother had sent her to check on some neighbors. Grace found the husband so sick that he was unaware that his wife had died in bed next to him. “It was terrible. It was really bad. The 1918 flu.” Grace told the interviewer.