Post written by Jenny Hannifin, Archive Research Assistant, and Doug Ernest, Archive Volunteer.

Join us on Thursday, November 8th, for World War I and Fort Collins: Exploring the John Hurdle Scrapbook in the OtterBox Digital Dome Theater to commemorate the “War to End All Wars” through the local lens of a remarkable scrapbook created by John Hurdle, a Fort Collins man who traveled to Europe and served on the Western Front with Artillery Battery A during The Great War.

Armistice:

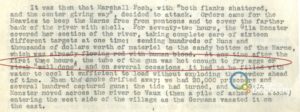

On November 11, 1918, an armistice with Germany was signed in a railroad carriage at Compiègne. The ceasefire went into effect at 11am, and for the soldiers of Battery A, the war was effectively over.

“There was none of the cheering or the excitement, crying, weeping, hugging and slapping of shoulders that you would want to see. It is hard to express our feelings. We were tired.” Fort Collins Weekly Courier, December 27, 1918

H12036: WWI Red Cross Nurses in Parade on College Avenue, Fort Collins, Colorado, 1917

The fighting may have been over, but it would be many more months before the soldiers of Battery A returned home to Fort Collins.

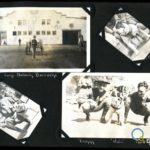

Soldiers of the 66th Field Artillery Brigade (which included Battery A) were part of the occupation force in Germany. They spent a few weeks in Blercourt; on Thanksgiving were served a huge traditional dinner; on December 2 departed for Germany; and celebrated Christmas Day in Germany by opening six kegs of beer. They remained in the town of Hohr-Grenzhausen, near Koblenz, until late May 1919.

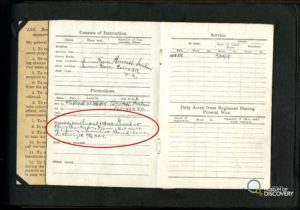

H00350: Charles Conrey (circa 1910), killed in action during WWI

Stories in Fort Collins newspapers in 1918 and 1919 reported the deaths of three men of Battery A. Charles Conrey was killed in action on October 10, 1918. Jesse Martin and Frank Niemeyer died of pneumonia while the unit was still in Europe. In addition to these three, John Hurdle’s album lists four other casualties: Louis H. Pinkham, Charles C. Moore, James Orendorf, and Walter G. Ridgeway.

“LeRoy Hafen’s Colorado and its People, Volume 1 (1949), page 540, reports that ‘1,009 [Colorado military personnel] were killed or died in service.’ … Many died of disease, including Walter Ridgeway of Battery A, felled by tuberculosis. … Ironically the number of war dead paled in comparison with the more than 7,783 Coloradans who died during the influenza pandemic which dealt death around the world mainly between September 1918 and early 1919.” (Colorado World War I Centennial Commission)

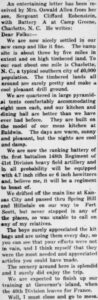

Battery A soldiers left Germany for France on May 26, 1919; departed France on June 3; and arrived in New York City on June 15. At Camp Mills, on June 19, their regiment was disbanded. Batteries A, B, C, D, and E arrived at Colorado Springs on June 24 via train, and “the Regiment marched in parade amid the shouts and praises of the entire populace.” From there the soldiers went on to Denver, Fort Collins, and Cheyenne, where they received similar welcomes “and the appreciation from the citizens of our record on the fields of France.” By the end of June the batteries had been discharged from military service.

To learn more about what happened to our Fort Collins soldiers AFTER World War, check out the resources below. And visit the Archive!

Resources:

- “Glad Peace Tidings Bring Joy Untold To Fort Collins – Entire City Is One Mass Of Flags Joy Hilarity And Song” : A report of the World War I armistice celebrations in Fort Collins and Loveland, Colorado on Nov. 12, 1918.

- Hurdle Scrapbook Scans

- Colorado World War I Centennial Commission

- Mentions of John Hurdle (post war) on the Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection

- E. Hurdle opens fine new offices, July 28, 1919

- E. Halliday having fine home erected, August 7, 1919

- French government diplomas to be awarded Sunday, February 18, 1920

- Organization National Guard Battery, April 26, 1920

- Elks arrange Flag Day Program, June 10, 1920

- American Legion meets for first time this fall, November 5, 1920

- Marriage license issued for John Hurdle and Marcia Shepardson, November 23, 1920

- Hurdle-Shepardson Nuptials at Greeley, November 23, 1920

- Fish Killer Dynamites Pool to Obtain Trout, August 11, 1921

- Pall bearer for Charles Conrey’s funeral, October 19, 1921

- Mr and Mrs Hurdle visit Frank Miller at Trails End, August 25, 1922

Continue Reading