Post written by Alex Ballou, Marketing & Design Assistant.

National Authors Day

Fort Collins Museum of Discovery had the honor of interviewing local author, Barbara Fleming. Barbara, a Colorado native, was interested in history and reading historical novels at a young age. When she went to college at Colorado State University, she studied English and writing. Barbara then ventured out to work as a journalist, teacher, and finally found herself writing books of her own in the 1980s.

Barbara sat down with staff for an interview in honor of National Authors Day on November 1st. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

- Tell us a little bit about yourself and your connection to FCMoD?

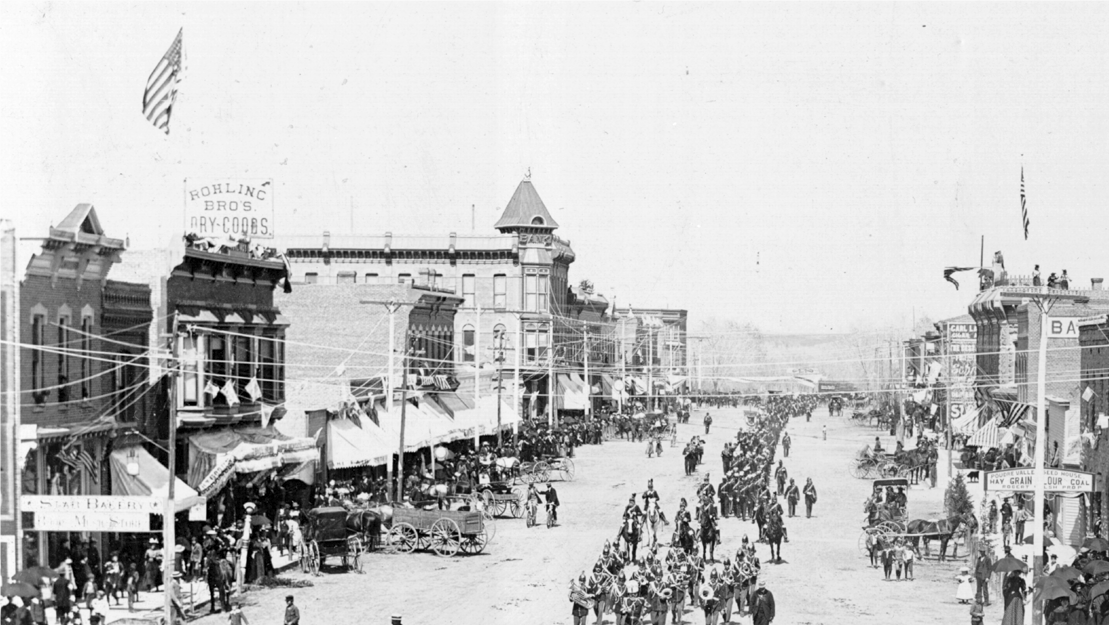

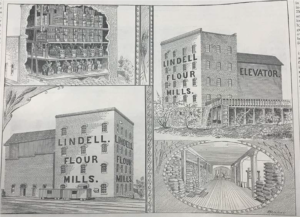

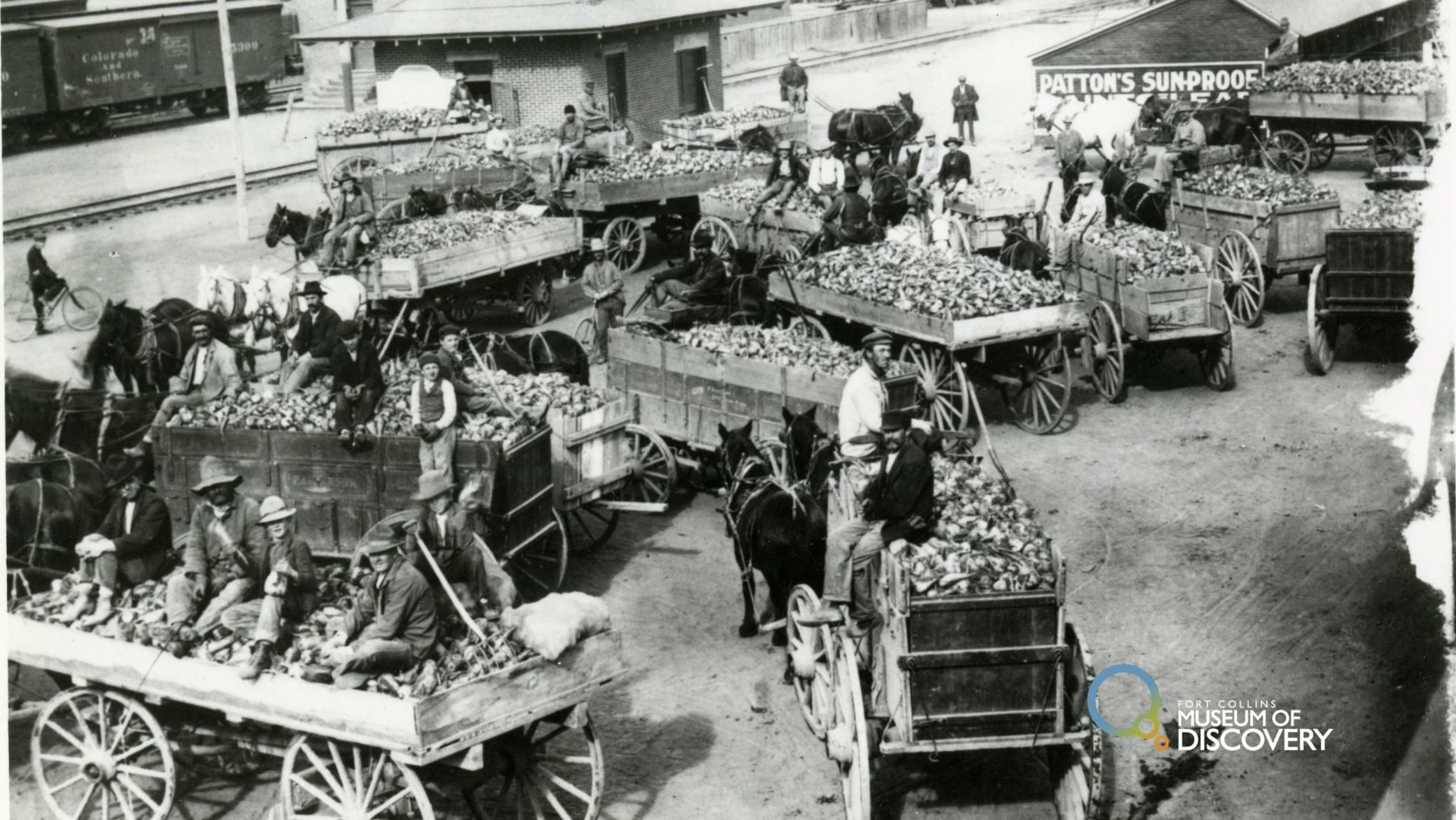

I am a native of Fort Collins. I have always been a lover of history. When I retired, and we moved back to Fort Collins, my late husband and I, I started writing the historical column for the now Fort Collins Weekly which became Fort Collins Now, in the meantime I had been contacted by a company called Arcadia publishing about writing historical books. So, I got together with a friend of mine, Mac McNeill, and we put together Fort Collins: The Miller Photographs and in the course of writing that I got even more interested in the history of my hometown because it is rich and fascinating. So, when the Weekly went out of business, I contacted the Coloradoan and started writing the column for them. Doing that brought me to the Archive multiple times before and after it was moved to the Fort Collins Museum of Discovery (FCMoD). I was well acquainted with [the archivists] back in the basement of the Carnegie building, where the Archive used to be, and am still now acquainted with the archivists at FCMoD. So, I have been coming to the Archive for a very long time.

“The history of [Fort Collins] is rich and fascinating.”

- What inspired you to become a writer?

I was always a writer. I started writing, almost, well actually before I started school and I taught myself to read when I was four years old. When I was young I was going to be like Jo March from little women – I was going to be sitting in a garret and eating apples and writing famous books. Didn’t quite work out that way, I had to earn a living, so instead I started teaching English. I did write a book in 1983, which is called, Fort Collins a Pictorial History, which is a hard-back book that is now out of print. And subsequently I wrote from time to time about various topics for various publications. It was not until I came back here that I started to devote more time. I went to college at CSU. My late husband Tom and I lived in Denver for a time and I taught at various community colleges as an adjunct English teacher. But I was always a writer.

- How did the process of writing your first book, Journeying, go?

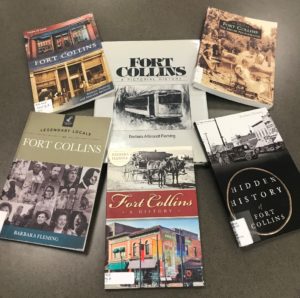

Journeying was the first book I published without a co-author. Then I published a couple more: Legendary Locals of Fort Collins, Fort Collins A History, and Hidden History of Fort Collins. The process included a lot of research, and a lot of pondering. But when I write a novel – and I have written several, even though only two have been published – I just wait for the characters to find out what they are going to do, that’s hard to describe if you’re not a writer, but writers understand that. Journeying is historical fiction. The others I have written are more contemporary, but who knows if they will ever see the light of day, it’s hard to say.

- Now that you’ve been published, is there anything you wish you would have known before?

I think any writer can look at anything he or she has published and would like to do it all over again. We can see the flaws even if other people can’t. But, no, when your writing you reach a point that I quit that’s it and enough is enough and you let it go because you have to. So, no there is not anything that I wish I would have known before.

- What are some books you would recommend for locals to learn about Fort Collins history?

History of Larimer County Colorado by Ansel Watrous – it’s not a book you sit down and read, but a book you can take in bits and pieces of. And a book that ought to be in any serious historian’s library. And Fort Collins Yesterdays by Evadene Swanson as well as and John Gray’s book The Story of Camp and Fort Collins: Calvary and Coaches, which I would love to own (but if I got it through ebay or somewhere it would cost me almost $300 so I can’t do that). The Wrecking Ball of Progress by Wayne Sundberg is a good video to understand about historic preservation. The museum has done a video about the history of Fort Collins and that’s a good one too. I don’t listen to podcasts so can’t recommend one. There is a digital newspaper state collection online, Colorado historic newspapers, which goes from beginning of newspapers of the 1860s to 1924, that they have all been digitized.

- What role would you like to see museums like FCMoD play in helping prepare young people for a career in STEAM related fields?

Anything that can get them engaged is of value. Young people are – well I can’t make generalizations – I feel young people can be somewhat disaffected, and not as involved with the world around them as we – or I – would like them to be. Anything a museum, or anyplace really, does that reaches young people and encourages them to be engaged and hands-on is of value. The arts are critical to the survival of a culture. We need art.

“Anything a museum does that reaches young people and encourages them to be engaged & hands-on is of value.”

- FCMoD’s archive has multiple of your books in our collections. How does it feel to have your story preserved in a museum?

I think it’s very gratifying. I think the more information we can share about history the better. To me, history is not just dates and events – and that’s the way it is usually taught. And so, a lot of people say they hate history and say it is boring. History is people and their stories. And so, I don’t record history. I tell stories. And there is a huge difference between the two. So, I am pleased if my stories are there for future generations.

- What do you wish people would ask you about writing?

Hmm… I think rather than having people ask me about writing, because it is such an individual task, I would like to be able to encourage people to write, whether they think they are good writers or not, because everyone has stories to tell and we ought to share our stories. So even if you do nothing more as an older person than write out significant events in your life, you are telling a story and that is what is important. I would love to think that such ideas and information are being shared by younger generations. One of the things I do is through the Partnership for Age- Friendly Communities- a formal nonprofit organization. They publish a blog once a month called Graceful Aging that is written by older people whose stories are told about their experiences of aging. Our goal is to reach young people to help them understand what it feels like to be old and what kind of experiences we had and what we share; to touch them in some way.

- Here at FCMoD, we tell the stories of Northern Colorado. Part of the museum’s vision is to inspire inquisitive thinkers. What advice do you have for the future journalists, writers, authors and dreamers of the world?

Well for writers, first of all, write about what you know, write from your own life and experience and it will expand as you begin to write to the world around you.

For dreamers, I think anything is possible, the world is changing so rapidly, so intensely, that we sometimes, I feel that I am on a merry-go-round, going around and around, faster than I can keep up with. I think you just have to grab the brass ring and believe anything is possible… because look how far we’ve come.

In my lifetime, it’s astounding, we have gone from communication by telephone – when I was growing up we had a party line – to this; to the internet. It is astounding what has happened, even in the last twenty years. I think it is because people keep dreaming, and I think people need to keep dreaming. Writers should know though that making a living writing is tough, really tough. I couldn’t live on my writing. I travel on it, but I couldn’t live on it. Unless you’re really lucky or if you’re JK Rowling or James Patterson, you’re not going to make a living. But that should not deter them from writing because there are always stories to share. And I think we do not share enough.

“I think you just have to grab the brass ring and believe anything is possible… because look how far we’ve come.”

Thank you to Barbara for her time and for sharing her stories!

To find out more about Barbara’s books and to hear more from a local author follow: www.authorbarbarafleming.com

Barbara will also be at a book signing December 1st at JAX Outdoor for their annual author day celebration.

Continue Reading