Post written by Jenny Hannifin, Archive Research Assistant.

Did you know that scientific research using the humble sugar beet led to the birth of microbiology?

In the 1800s, agriculture and manufacturing industries struggled to meet the demands of a growing and changing population. Science was applied rigorously to solve domestic challenges, and the “industrialization of agriculture was reflected in the growth of the sugar beet, fermentation and other food industries.” (Needham, p. 189) Scientists in the mid-1850s wanted to understand the chemical nature of living matter, not only for the betterment of agriculture, but for the sake of pure science.

Louis Pasteur (1822 –1895), famous for his vaccines and processes of sterilization, began his career by studying the crystalline structure of organic substances. He believed that asymmetrical structure, which produced optical activity (the polarization of light), was related to life itself, and that processes like fermentation worked because the substances involved were alive (what we now call microbes or microorganisms). Pasteur taught his students the principles of bleaching, sugar refining, and fermentation, including the processes used in the manufacture of beetroot alcohol.

Sugarbeets were a big industry in France, and one of the Lille distilleries asked Pasteur to help them solve a problem they were having with spoiled product. Pasteur analyzed the fermentation processes that he observed at M. Bigo’s sugarbeetroot distillery (circa 1856), and tied those observations to his research on the asymmetry of living substances.

What began as a search for the cause of spoiled beet alcohol led to a full-on investigation of fermentation. If the products of fermentation were alive, as Pasteur thought, then fermentation was a living process, not one of decay, as was believed by many scientists at the time.

But if that were true, where did that life come from? Could it spontaneously generate, as some believed (Pasteur thought not)? Fermentation was at the root of important scientific debates at the time, and investigating questions like these heralded the beginning of microbiology (the study of microscopic organisms).

Pasteur eventually proved that microbes in the air we breathe kick-start many processes (like fermentation) that are inherent in organic matter. Pasteur also determined many important principles about living microbes; for example, that microbes infecting animals caused disease, the so-called “germ theory” of disease.

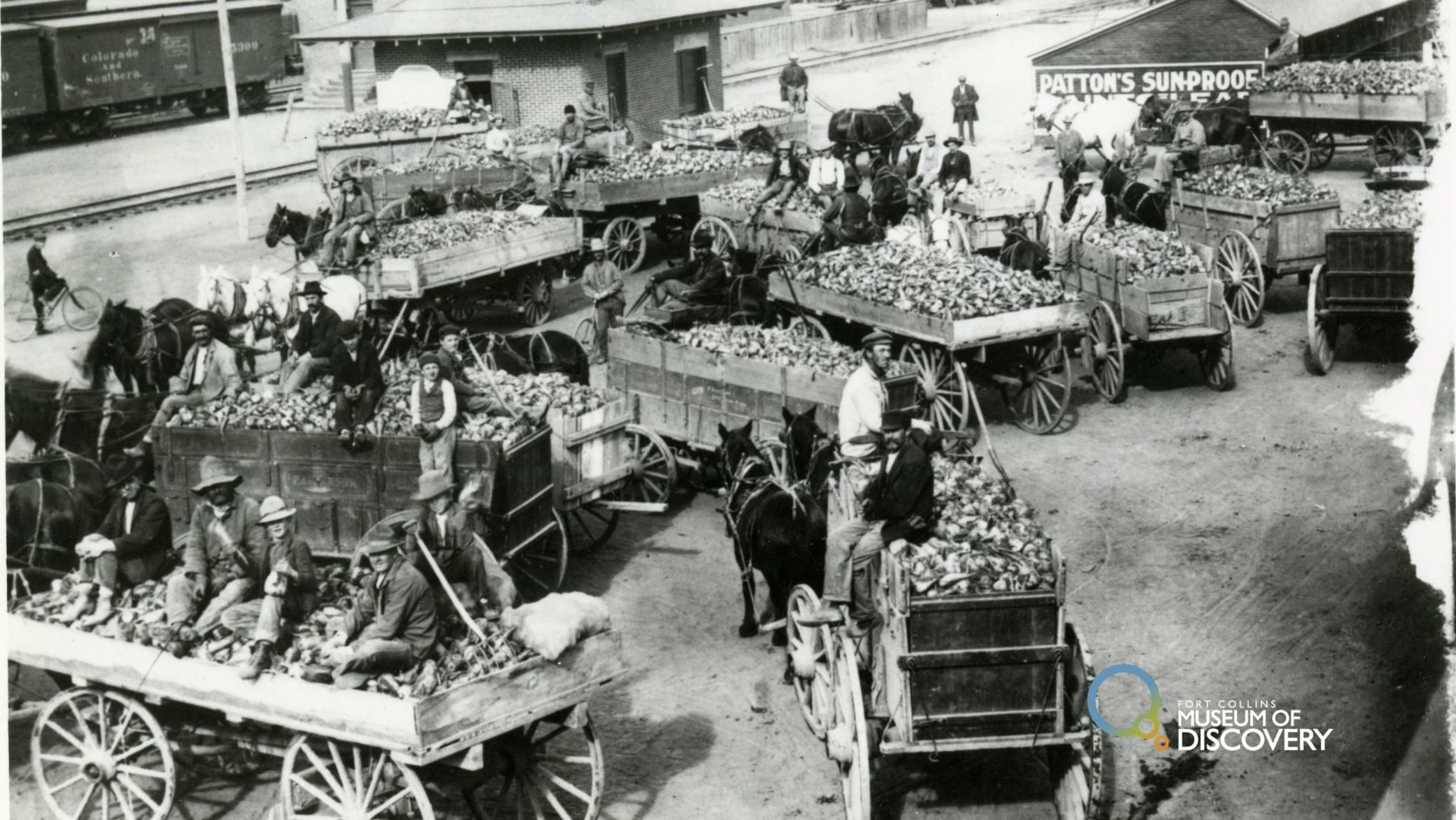

Image: Wagons bringing in sugar beet harvest to C&S Depot on Mason Street, Fort Collins, Colorado, circa 1902.

Sources:

- Needham, Joseph (ed.). The Chemistry of Life: Eight Lectures on the History of Biochemistry (1970: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge).

- Geison, Gerald L. The Private Science of Louis Pasteur (1995: Princeton University Press, Princeton).