Post written by Jenny Hannifin, Archive Research Assistant, and Doug Ernest, Archive Volunteer.

During four months in combat in World War I, Battery A took part in three major battles: the Second Battle of the Marne (July 15–August 6), the Battle of St. Mihiel (September 12–16), and the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne (September 26–November 11). The Meuse-Argonne remains the largest battle ever fought in American history, with 1.2 million American troops involved and a casualty roll of approximately 122,000 dead and wounded.

It is no exaggeration to say that the Fort Collins soldiers of Battery A had a significant role in World War I.

At the Second Battle of the Marne (also known as the Aisne-Marne Offensive) Battery A saw their first dead and wounded soldiers from both sides of the conflict, witnessed enemy aircraft circle overhead, and suffered deadly gas exposure.

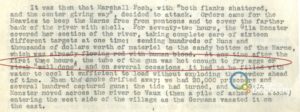

In his history of Battery A’s Grande Puissance Filloux artillery piece, aka “Gila Monster,” Hurdle tells us that at the start of the German offensive, the GPF was in action for 72 hours. The barrel grew so hot that it could have fried steak and eggs and at times had to be filled with water to cool it.

The troops’ efforts in July and August of 1918 would significantly impact the future of the war. Whereas in the spring and early summer of 1918 the Germans had been on the attack, hoping to defeat the French and British before American troops arrived, the Second Battle of the Marne reversed that situation. From August 1918 until the end of the war, the Germans were on the defensive, and the Allies always moving forward.

An anonymous letter from a member of Battery A to the Rocky Mountain Collegian reported: “We counter-attacked right in the center of [the German] push, men met men, and after the hell stopped we held the River Marne’s south bank, and Paris, if not the world, was saved.” (“Battery A Actively Engaged in Fiercest of American Drives,” Rocky Mountain Collegian, January 2, 1919).

In a letter to The Weekly Courier (published August 16 but dated July 12), Hurdle writes “the doughboys here tell us that when the gas comes over, there are just two kinds of soldiers, ‘the quick and the dead’ … ” (page 2.)

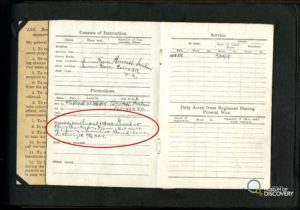

Unfortunately, that deadly gas could spread almost instantaneously, and Hurdle was caught by it on August 10, near the village of Chery-Chartreuve. Though in serious condition due to gas exposure, he refused to be evacuated. His military Record Book shows him as having participated in battles until August 16, 1918, but not thereafter. It seems likely that the Army sent him to a rear area not just for further officer training (he had been promoted from corporal to sergeant in the summer of 1918), but also to allow him time to recuperate from the lingering effects of that terrible gas exposure.